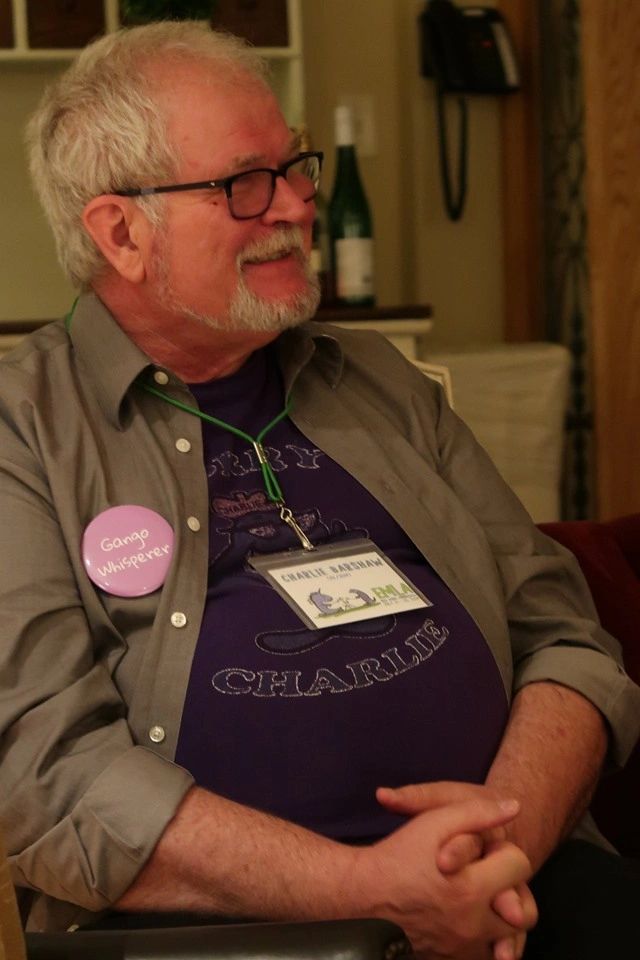

Author, Presenter, Writer of Stuff

Welcome

Welcome

Seven short stories with Amazon Rapids Reading App.

NUTS, Cayden's Car and Superstition, all MG manuscripts in various stages of completion.

BURIED (Formerly called Aunt Agnes), Brandon Inn Ghost Story

Ruth and I visited hundreds of schools over the last decade. We'd love to visit yours.

As a member of the MRA, I promote literacy and reading throughout our great state.

.jpg/:/rs=w:388,h:194,cg:true,m/cr=w:388,h:194)

A member since 2009, I've worked on the Advisory Committee to chair conferences, worked as a Shop Talk group leader, and write for The Mitten blog.

The Writer Spotlight is a regular column in The Mitten blog, the Society of Children's Book Writers and Illustrators, Michigan chapter (SCBWI-MI). In it I conduct interviews with (mostly) Michigan-based children's book creators, writers, illustrators and editors.

Check out some recent interviews with children's book writers and illustrators.

Apparently you have to copy the link and open it in another tab.

Rick Lieder

Rick is a renaissance man, a macro-photographer and artist.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2024/09/featured-illustrator-rick-lieder.html

Kelly Dipucchio

Kelly is a prolific picture book writer who has now got an animated series on PBS.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2024/08/writer-spotlight-kelly-dipucchio.html

Helen Frost

Helen teamed her nature poetry with Rick's close-up photos in a number of well-loved books.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2024/08/writer-spotlight-helen-frost.html

Rhonda Gowler Greene

Rhonda is a veteran picture book writer with dozens of titles.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2024/10/writer-spotlight-rhonda-gowler-greene.html

The Writer Spotlight is a regular column in The Mitten blog, the Society of Children's Book Writers and Illustrators, Michigan chapter (SCBWI-MI). In it I conduct interviews with (mostly) Michigan-based children's book creators, writers, illustrators and editors.

Check out some recent interviews with children's book writers and illustrators.

Apparently you have to copy the link and open it in another tab.

2025 SCBWI-MI Spring Conference Faculty

John Hendrix

John is a multi-published, award-winning author and illustrator, who headlined the conference.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2025/03/scbwi-mi-spring-conference.html

Debbie Gonzalez

Deb is a native Texan, published author and Pinterest Queen

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2025/03/scbwi-mi-spring-conference-presenter.html

Kat Higgs-Coulthard

Kat is an educator with two published novels. She is also part of the faculty.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2025/04/scbwi-mi-spring-conference-presenter.html

Sarah Rockett

Editor of Sleeping Bear Press and Tilbury House books.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2025/04/scbwi-mi-spring-conference-presenter_0366685763.html

Carrie Pearson

Carrie, former SCBWI-MI RA and multi-published pb writer.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2025/04/scbwi-mi-spring-conference-presenter_0252828794.html

Here's the original interview with Carrie.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2023/05/writer-and-regional-advisor-spotlight.html

Maria Dismondy

Maria is an author and publisher of Cardinal Rule Press.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2023/05/writer-and-regional-advisor-spotlight.html

Check out some recent interviews with children's book writers and illustrators.

Apparently you have to copy the link and open it in another tab.

The 2014 Conference Faculty

Arthur Levine

Arthur is an editor and published author and a faculty member at a 2014 conference.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2024/11/editorwriter-spotlight-arthur-levine.html

Candace Fleming

Candace is a prolific writer in all genres.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2024/12/writer-spotlight-candace-fleming.html

Eric Rohmann

Award-winning author and illustrator, and married to Candy.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2025/01/authorillustrator-spotlight-eric-rohmann.html

Christy Ottaviano

Longtime editor, now with her own imprint. Also Laurie's editor.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2025/02/editor-spotlight-christy-ottaviano.html

Laurie Keller

Author and illustrator, also a faculty member of the 2014 conference

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2024/11/authorillustrator-spotlight-laurie.html

2014 SCBWI-MI Mackinac Island conference

I was fortunate enough to co-chair this conference. A look back on the 10th anniversary.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2024/10/mackinac-island-conference-2014.html

Memories of Mackinac

Attendees share what they remember at the 10 year anniversary.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2024/12/memories-of-mackinac-island.html

Check out some recent interviews with children's book writers and illustrators.

Apparently you have to copy the link and open it in another tab.

Rhonda Gowler Greene

Rhonda is author of dozens of picture book titles

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2024/10/writer-spotlight-rhonda-gowler-greene.html

Sarah Miller

Young Adult non-fiction biographer and historian

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2024/06/writer-spotlight-sarah-miller.html

Matt Faulkner

Author/illustrator of picture books and graphic novels

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2024/05/authorillustrator-spotlight-matt.html

Kristen Remenar

Author of picture books, who married Matt and overcame a stroke.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2024/05/authorillustrator-spotlight-matt.html

Check out some recent interviews with children's book writers and illustrators.

Apparently you have to copy the link and open it in another tab.

Lynne Rae Perkins

Lynne is the author/illustrator of picture books and middle grade novels

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2024/04/writer-spotlight-lynne-rae-perkins.html

Jeff Stone

Jeff wrote two middle grade series with a major publisher, now owns the rights

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2024/03/writer-spotlight-jeff-stone.html

Lisa Wheeler

Prolific author of dozens of picture books.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2024/02/writer-spotlight-lisa-wheeler.html

Heidi Sheffield

Award-winning author/illustrator who overcame cancer.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2024/05/authorillustrator-spotlight-matt.html

Check out some recent interviews with children's book writers and illustrators.

Apparently you have to copy the link and open it in another tab.

SCBWI-MI 2013 Weekend Retreat

I was co-chair of this unusual conference.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2023/09/the-2013-scbwi-mi-conference-or-what.html

Conference Attendees Remember

Stories from those who were there

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2023/10/attendees-remember-2013-conference.html

Conference Faculty Remember

Deborah Halverson and Audrey Vernick recall 10 years ago.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2023/11/the-presenters-speak-2013-conference.html

Audrey Glassman Vernick

Author of middle grade novels and picture books was a 2013 presenter.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2023/12/writer-spotlight-audrey-glassman-vernick.html

Deborah Halverson

Deborah writes, edits, and presents. She led writers in 2013.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2023/12/writer-spotlight-deborah-halverson.html

Check out some recent interviews with children's book writers and illustrators.

Apparently you have to copy the link and open it in another tab.

Lindsey McDivvitt

Lindsey faced unemployment when she switched her career to writing.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2025/01/writer-spotlight-lindsey-mcdivitt.html

Lori McElrath Eslick

author and illustrator Lori Eslick fought back from an aneurysm to win art awards.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2025/01/featured-illustrator-and-author-lori.html

Isabel Estrada O'Hagin

A revisit with author Isabel.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2025/03/writer-spotlight-isabel-estrada-ohagin.html

Here's the previous interview with Isabel

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2022/04/writer-spotlight-isabel-estrada-ohagin.html

Leslie Helakoski

Leslie is an author and illustrator with many picture books.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2025/04/featured-illustrator-leslie-helakoski.html

Darcy Pattison

Darcy is an author, runs Mim's House Publishing, and does presentations with Leslie.

https://scbwimithemitten.blogspot.com/2025/05/writer-spotlight-darcy-pattison.html

In the Summer of 2016, Ruth's agent asked her if she'd be interested in a freelance job writing for children.

Intrigued, she agreed, and was contacted by an editor creating a reading app for children 7-12 .

The catch was that the stories had no description, simply dialogue between or among characters, and the story itself totaled 1000 words or less.

I played with the constraints, came up with dozens of pieces. Ruth chose four of her favorites, edited, revised and sold them.

She then asked the editor if he'd work with me, and he said, "Yes!"

So, I edited, revised and sold three stories under my own byline.

Since then, they've stopped using freelance writers, but I've been published and paid.

And apparently you can't get to Amazon Rapids from here. Most of the google searches are dead ends.

But if all else fails, I have copies of some of the edited words.

Here's whichever one I find first:

`

Charlie Barshaw

5816 Schafer Road

Lansing, MI 48911

517.393.6218

Story Word Count 888

Two avatars: Clarice and Princess Buttercup

Fantasy, ages 10-12

Face-to-face conversation

Protagonist: Clarice

UNICORN PACKAGE

(Illustration: Unicorn in girl’s bedroom, lifting the covers off with her horn. Sleeping girl is annoyed.)

Unicorn

Hey, girl. Your heart’s desire has been delivered, or some such nonsense.

Clarice

Gah! Who? What?

Unicorn

I’m your wish. Every night, for more than a year, you’ve been all “Unicorn, unicorn, unicorn.” So look what just pranced in: A horse with a growth on its head.

Clarice

But that was back when I was five years old. Everyone wished for a unicorn then.

Unicorn

I know, right? Big demand. Back ordered for years.

Clarice

Seven years. That’s more than half my lifetime.

Unicorn

Unicorns take time, honey. You wanted and wanted. Now you got.

Clarice

I can’t be held responsible for a wish when I was five. I was just a child.

Unicorn

Legally binding. I am your pet, come hay or high water.

Clarice

Nopedy-nope nope! A unicorn isn’t even on my wish list anymore. Now I need a nose ring. And a butterfly tattoo on my ankle.

Unicorn

Nay, don’t see those happening anytime soon. Not with your uptight folks.

Clarice

Think they’ll be a little uptight about a full-size horse in my bedroom?

Unicorn

It is tight in here... Speaking of, where do I sleep?

Clarice

Not happening. Go back to your rainbow kingdom in the clouds.

Unicorn

Girl, are you pulling my fancy tail? There’s no cotton candy unicorn world.

Clarice

Five-year-old me thought so. I also thought you’d be more pony-sized.

Unicorn

I may be magical but I can’t read your mind. You ordered a horned horse, you got one.

Clarice

Did you just take a dump on my carpet?!

Unicorn

Yep. Magical stuff. Looks like marshmallows and glows in the dark.

Clarice

Like fluorescent candy?

Unicorn

It’s still poop, so don’t you go eating any.

Clarice

And what kind of horn is that? You look more like a rhinoceros.

Unicorn

Awful close to personal territory there. Unicorn was yourdream.

Clarice

My dream became my nightmare.

Unicorn

Ha. It’s night. I’m a mare of sorts. Very witty.

Clarice

I never really wanted you. I was just horsing around in my imagination.

Unicorn

People think they need so many things. When they get them, then they need something else.

Clarice

Well, now I need you to leave.

Unicorn

Ouch. Even magical creatures have feelings…

Clarice

Sorry. We kinda got off on the wrong, um… horseshoe. You just caught me by surprise.

Unicorn

I gotcha. You’re stunned that your seven-year-old wish came true tonight.

Clarice

Yeah. And it’s cool that you’re mythical and magical and all…

Clarice

…But there just isn’t enough room.

Unicorn

I get it. You need your personal space, and I’m ten pounds of feed in a five pound bag.

Clarice

What’s your name, anyway?

Unicorn

Are you funnin’ me? What’s my name? Your five-year-old self named me.

Clarice

Honestly, I don’t remember.

Unicorn

Every night for more than a year? The name started out simple, but it grew and grew.

Clarice

Wait... was it Princess Buttercup?

Unicorn

Keep going…

Clarice

Princess Buttercup von Sparkleduster?

Unicorn

Keep going…

Clarice

Sigh. Princess Buttercup von Sparkleduster Happy Dancer the third.

Unicorn

Yep. That’s the name you hung me with.

Clarice

I am so sorry. But really, I was five. I even named my shoes lefty and righty!

Unicorn

Keep going…

Clarice

Lefty Lucy and Righty Tighty.Because they were.

Unicorn

I admit, that’s cute. Still, five-year-old you created seven-year-old me. In horse years, I’m practically middle-aged.

Clarice

So… how can I un-wish you?

Unicorn

That’s a slap on the rump. You want to undo your wish-come-true?

Clarice

Please don’t be hurt. You’re everything a five-year-old girl could want. I’m just not five anymore.

Unicorn

There is ONE way to reverse the wish, but you’ll have to take a deep, dark look inside yourself.

Clarice

I’ll do it. I’ll try anything.

Unicorn

You come give Princess a big hug. Then you rub my horn and you say my name three times fast.

Clarice

You are a nice unicorn, you know. I really did want you back then.

Unicorn

Just say it.

Clarice

Princess Buttercup von Sparkleduster Happy Dancer the Third. Princess Buttercup von Sparkleduster Happy Dancer the Third... Ooh, I’m out of breath.

Unicorn

One more. And I hope you’ve learned your lesson about wishes.

Clarice

Princess Buttercup von Sparkleduster Happy Dancer the Third.

[IMAGE of unicorn disappearing in a rainbow-colored puff of smoke?]

Clarice

I can’t believe all that wishing business works!

Clarice

Hmm…

Clarice

Ahem. I wish for a unicorn ankle tattoo….

With published authors, storytellers, teachers and writers of all stripes, this collection of creators is invaluable.

*It's our opinion, and we're sticking to it.

While attending a national writer's conference in Los Angeles in 2015, chance united me with these four writers.

We continue to meet periodically to this day on Google Hangouts.

A local writing conference and a short-lived online critique group led me to work with Editor Teresa Crumpton of Author Spark.

She's been amazing at punching up my writing.

Because even though some of it is embarrassing, that's how one grows.

Parody newspapers, literary magazines, local magazines and newspapers and much more.

Coming soon, after I dig it up.

Good to have these all together in one place, for someone's amusement.

Preparing this one for beta readers and submission. It's been on my mind since 2014, and you can see the changes in story approach in these first pages.

This was the first novel I ever wrote. Recently departed from my retail career, I wrote the first draft in the Summer of 2009. It's gone through so many drafts since that I've lost count, but I haven't lost hope that it might someday reach a reader's eyes.

Check out some first pages of this, too.

Still can't figure out whether this one is an older middle grade or a young young adult novel. I started this one in the Fall of 2009, after I decided I'd rather start a new story rather than revise Cayden's Car. I lost all of my previous drafts, but found a hard copy of the entire novel (!) It's still in the drawer, but I've got a few first page attempts.

“Maybe,” I said to the lady cop, “it’s all misdirection.”

“I asked you where your grandparents went. Which direction is misdirection?”

Grandpa always said you had to figure out your audience, and I knew my audience was cranky. She might’ve been naturally that way, or maybe she didn’t want to be stuck on this old person missing person’s case.

I knew she was mad about the rope ladder being the only way to climb to the scene of the crime. Mom and I had to lug the creaky extension ladder from the garage. And she could’ve been angry about that, too, since it wasn’t much better.

And she’d really be really aggravated to find out I hadn’t changed my story since the last time I saw her. Because all I could remember when Gtrandpa and Grandma Arbour disappeared was a bright flash of light.

“Misdirection is for magic tricks,” I said. I looked at my close-fisted left hand while I reached for her head with my right hand.

She grabbed my wrist, and the quarter I was sliding up my fingers to pull from her ear squirted from under my thumb and popped her in the eye. At least I knew for sure why she was pissed now.

“Ow,” said the lady cop, squeezing my wrist. “You assaulting a police officer?”

“I was showing you misdirection. You’re supposed to look where I’m looking, at my balled-up hand,” which was turning pale as the blood stopped running to it. She let go of my wrist so she could rub her eye. I flexed my fingers and shook my hand to get the circulation going again. “Good reflexes.”

“Chase,” Mom said. “This is no time for fool’s play. Just answer the question.”

{Insert new Chapter One. Policewoman is in treehouse with Chase and his Mom, asking about the disappearance of Grandpa and Grandma Arbour. Chase can’t remember anything other than a white flash. Cop is skeptical about Chase’s version, irritated that it was so hard to get into the treehouse, and generally ticked she gets these kinds of rinky-dink missing person cases. The official stance seems to be that Grandpa ran off with his deteriorating wife. In fact, a pair of overalls were stolen from a clothesline. Theory is he disguised the two of them.}

Chase tries to pull a coin out of ear, but fails. As she leaves, she pulls her business card out of his brillo mop of hair.}

Shelley was nuts. Trust me, I knew nuts. It kind of ran like a squirrely grandpa through my family.

Sixth grade girls were inscrutable, sure. Gathering in giggling gaggles to whisper and cast furtive glances, they were just hard to figure. And they oozed sarcasm. I had to look that word up to be sure, but there was no mistaking that knife-edged tone of snark. Not that they whispered, cast or oozed at me: they ignored me like I wasn’t there.

But that was normal-girl stuff. Shelley was not a normal girl. And what was definitely not normal was that she was attracted to me.

No, not like boyfriend-girlfriend. Sorry, I threw up a little in my mouth. More like she was a pile of metal shavings, and I was a big old magnet. And no matter how hard I tried not to attract crazy, I could not turn off that incessant pull.

It’s not politically correct to call mentally and socially differently-abled people crazy or nuts or loco or any other name. I figured I had a good excuse, because I was one of them.

I was about halfway up that twelve foot ladder when I remembered I was afraid of heights. It might have been the bouncy bend that creaky metal made with every one of my husky steps. Maybe the sharp-edged leaves, green with just a touch of yellow, that slapped at me like they really meant to see me fall.

Definitely it was the nasty gray squirrel, a notch missing from the top of its left ear, chattering and charging, then retreating, as I approached the tree house. Pretty much my tree house, now that Grandpa had disappeared, but as I swayed in the wind, gripping the metal rungs at eye level, I decided the squirrel could have it.

It wasn’t my favorite place anyway, not anymore. I helped Grandpa build it, and kind of forgot that I didn’t like to stick my tongue out at gravity, way up where one clumsy move and the hard ground reaches up to break your face. These were not the thoughts to keep me climbing, and yet the next thing I knew I’d grabbed hold of the railing of the tree house deck.

The ladder groaned and slipped, and in terror I grabbed hold of the wooden spindles and hauled my shoulders up onto the floor, my belly scraping along the boards as I dragged my top half onto the relatively solid planks. My legs scrambled after, almost knocking the ladder away from the trunk. It swung out, and then slammed back with a clunk.

I crawled toward the doorway and its promise of interior stability

Grandma’s calloused hand had softened, like the gooey edges of her mind, but she still had a grip. She crunched my fingers together as we approached the tree with our tree house in it. I’m pretty sure she was excited. I felt like adding the soggy cereal sloshing around in my stomach to the thin mat of party-colored leaves under the base of the tree.

Grandpa called it our tree house, as in, it belonged to me and Mom and Grandma and him. But Mom was too busy working to climb up, even if she wanted to, which she didn’t. She had no time for childish pleasures, she said.

Grandma wanted to, but we didn’t let her. That’s all she had time for now, childish pleasures, because her Grandma-brain had melted to a point where she was like the toddler sister I never had.

I didn’t want to climb up, ever, because my feet preferred solid ground, and so did the rest of me. I was terrified of heights, and I reminded Grandpa of that from the day he decided to build that monstrosity to this very morning.

No, the tree house was all Grandpa’s.

But the crumpled-up note in my jeans pocket had instructions that made me wonder whether Grandpa had caught Grandma’s dementia. Most eleven year old boys didn’t even know the word, but I lived it, left home, changed schools, lost every friend except my grandparents when we moved in with them.

I knew you couldn’t catch it like a cold, but the way Grandpa had been acting lately, muttering all night in his basement workshop, scuttling around behind haunted eyes, maybe he had the seeds of it in him, too. If so, what did that mean for me and my already forgetful brain?

I didn’t have to read Grandpa’s crunched-up handwriting to know what I had to do

I shouldn’t have opened the window. That was my first mistake.

No, my first mistake was right after school, when I slipped through the cornfield path that wandered to my grandparent’s house, and this loony girl with a big ratty nightgown tied up over her shoulder grabbed me. I mean, like pinched my elbow with two dirty fingernails until I had no feeling in my fingers, grabbed me.

Maybe I couldn’t have run away then, but I sure could’ve called the cops, especially when Shelley, that was the loony girls name, threatened to come get me that night. Except I’d end up talking to Officer Mikayla. I’m pretty sure the police officer was still pissed she’d had to climb that wiggly ladder to the tree house and then find out I couldn’t remember anything except a bright light explosion when

my grandparents disappeared.

Maybe my very first mistake was being born into this nutty family, my folks divorced, my Mom’s parents acting more like my parents. Until Grandma Marshalla started losing pieces of her memory, with Grandpa experimenting feverishly in his basement workshop on something to bring her back.

But can I call it a mistake when I don’t remember it? I mean, if I don’t remember making a decision, to be born,or to help my grandparents disappear, can it be my fault?

Still, I owned this particular mistake. The decision was, open the window with Shelley’s crazed face on the other side, or run and hide, wake my exhausted Mom up or call 911 and try to explain that a crazy girl had somehow crawled up the side of the house to scratch at the glass.

I burst into the house, forgot to shut the door. Forgot to hang up my coat and my backpack, forgot to wipe off my muddy shoes, fresh from the corn field.

I forgot to shout out hello, and when I got to Grandma and Grandpa’s bedroom door, I forgot to knock. I just blasted my way in, like an autumn wind before a storm.

It wasn’t normal not-doing-stuff, which everyone doesn’t do. I went back later, because I had an itch in my brain, and found all those undone things. I remembered that I forgot. And that was the problem.

Grandpa had his pipe between his teeth, his lips popping like a fish breathing the oxygen out of water. Grandpa startled, dropped the pipe, caught it at belly level.

“Hey, Chase. I wasn’t smoking it, just thinking.”

“Thinking about smoking?” I asked. My brain was off course already. “You promised Mom.”

“No, no. Just thinking about choices, and promises kept and not. Smoking’s a filthy habit, don’t you ever get started.” He wagged his pipe at me. It still smelled a little like apples and burnt leaves. “But it helps me think sometimes, with a really tough problem, to have this pipe in my mouth. Say hello to your grandmother.”

Grandma sat on the edge of the bed, rocking a little, back and forth, staring at her slippers. They were fuzzy green. She wore her favorite bathrobe, bright colored stripes of red, green and orange.

CAYDEN’S CAR

CHAPTER ONE (Trouble seeing)

I breathed some moist mist on the lens, then wiped my smudged glasses on the chest protector. I squinted into the deepening dusk, just barely making out the shape of the Breath Car and Dad.

Most of the lights in the parking lot were dead or broken, but my poor eyesight was the main culprit. I fitted the thick frames back over my nose, and found my sight blurred even worse than before.

Then a scene establishing the relationship between the narrator and his Dad. Cayden is a worry-wart. He knows he’s not a good mechanic. His accident in making the gizmo and the car function was pure luck, and he mostly has evidence, despite the monkey wrench from his Mom, that he sucks as a McAnnix. Yet he is willing to sacrifice his life to bring his family back together. He thinks he can fix that.

The Dad, Matt, is an optimist. He’s a good mechanic, a great inventor, but a little too free with his signature before signing documents. That’s helped to cause his current situation, broke, nearly homeless, unemployed (or self-employed). But through it all he is blithely cheerful and hopeful.

This scene establishes their situation, desperate, creating a little version of the car because they can’t afford to build anything bigger. That they called in a favor to get the car into the Auto Show, where Matt knows Mayor Harry Hizzonner. That it is a revolutionary invention that runs on spent breath.

CAYDEN’S CAR

CHAPTER ONE

TROUBLE SEEING

I grabbed the door knob, and it popped off in my hands. Dad had his head stuck under the washing machine lid, adjusting the engine, so I hurried up and snatched the monkey wrench from my back pocket. I replaced the knob, tightening the screw with the slotted blade attached to the bottom of the wrench.

I thought of Mom as I slid the wrench back into my pocket. Then I thought of some bad words when the knob came off in my gloved hand again. I gritted my teeth and gave the screw an extra quarter twist this time. My Dad was still puttering under the hood of the Breath Car.

A drop of sweat streaked the inside of my glasses lens. It was freezing out, but I perspired. That’s me all over. I breathed some moist air on the lens, then wiped my smudged glasses on the chest protector I wore. I fitted the thick frames back over my nose, and found my sight blurred even worse than before. That’s me all over, too.

We used a doorknob to open the car because we stole it off my bedroom door. That’s okay, because if this scheme of ours didn’t work out, I wouldn’t have a bedroom anyway. Besides, this wasn’t a normal car.

It was, instead, a little bitty go kart assembled from scrap, barely big enough for a kid to squeeze his short but wide body into. It was a rolling deathtrap.

CAYDEN’S CAR

"Call the police," said Dad. "Our invention's been stolen."

The mayor looked at Elle, who nodded curtly. "The police it is," he said. He cupped his hands over his mouth and yelled, "Oh police man!"

A burly fat man in a blue uniform with big gold buttons that strained at his bulging belly muscled through the door. He wore a tall hat shaped like a bullet and held a short club in his hand. He seemed to be a bad combination of a Keystone Cop and an English Bobby. This guy was just a thug in a cop get-up, no stretch for a mayor who wore nothing but costumes.

Illustration: fat man in a bizarre cop uniform

"What seems to be the problem here?" he rumbled, looking from my Dad to me with beady eyes in chubby cheeks.

"Someone stole our car," said Dad and I in unison.

"Serious charge," said the cop. "Describe this alleged vehicle."

"It's a little thing, only big enough for my son to drive."

"You let the kid drive? What is he, eight?"

"Eleven," said Dad.

"Almost twelve," I said. "The car's got mountain bike wheels on the front and a lawn roller on the back axle. Made out of spare parts, and it runs on breath. The Breath Car."

Illustration: The Breath Car in a voice bubble as Cayden describes it.

CAYDEN’S CAR: A chapter book mystery

CAYDEN’S CAR CAPER

CHAPTER ONE

I strapped on the too-tight bike helmet. Like everything else I wore, it didn’t fit. I had already velcroed on the goalie shin pads, buckled up the catcher’s chest protector and shrugged into the shoulder pads. I looked like a bunch of sports threw up on me.*

“Come on, Dad.” I pounded on my chest with muffled thuds. “This has got to be good enough.”

“Your back is unprotected.” Dad held up a puffy, striped pillow case. “I made this into a cape full of packing peanuts.”

“Just what are you worried about?” He and I had built this car from the mountain bike wheels in front to the lawn roller in back. What’d be safer than something built with our own hands? I have the Dad as a worry wart, and Cayden as the genius inventor in this version. Later, I have Cayden as a klutz, and not trusting his own work. Need to find each character their proclivities.

“Oh, I don’t know. I could be concerned because I’m trusting my twelve year old kid, my only kid, to drive a car, made out of scrap, which until yesterday didn’t even move?” I touched the doorknob on the car door, and it came off in my hand.

I reached into my back pocket for my customized monkey wrench. It had started out a regular adjustable wrench. I had added fold-out screwdriver blades, a full set of allen wrenches and a pry bar. I could buy an all-purpose tool, but it wouldn’t be a gift from my Mom five years ago. It wouldn’t have the monkey’s face she had drawn on the head of

I despaired when my "Superstition" folder came up empty, but I found a hard copy. Now I just have to copy it or type from scratch.

SUPERSTITION CHAPTER ONE

The ball was launched right at my face at about a hundred miles an hour because Wil didn’t do anything halfway. We were about 90 feet apart, but Holy Moses that ball gobbled up the distance fast. I had my glove up, but knowing Wil, there was a twist and sure enough, right at the last moment it dipped and veered outside. I don’t think baseball even had a name for that pitch, so I called it “Wilpower.”

Maybe I’d write it in my will, so at least Wil’d have something from me.

I rifled the ball back, though my aim was short and it took a bounce before hitting the glove. Who could throw right, with the kind of stuff swirling around in my brain?

“So, my birthday’s tomorrow,” I said. I took another high, hard one in the palm of my glove. There wasn’t much padding left there.

“What is that?” said Wil. “A hint? I never get you anything anyway.” Wil leaped into the air to spear my errant overthrow before it busted a neighbor’s window.

‘You know I was born on Friday the 13th,” I said. Wil changed the pace, floated a knuckleball at me that took an hour to snuggle into my glove. And then I dropped it.

“Yeah, I got it. Unlucky day,” Wil ranged far to the left to corral another of my tosses. I should just give up this game of catch. Though, to be honest, it wasn’t much worse from the way I normally played.

“Way worse than that, “ I said, as I snared another hard-thrown ball. Sheesh, that stung. “It’s like a devil’s curse, like the person is bound to be unlucky their whole lives. Like a black mark on my soul.”

Submitted to an agent after years of dawdling. Take a look at the various openings I tried.

A new project, based on a writing conference where the hotel owner admitted to having ghost children running through the mirror.

Just the barest of bones idea of a young hitchhiker who runs afoul of a serial killer trucker.

Sweat dripped down the hair pasted on my forehead. I shoulda taken the old bag up on her offer to buzz cut me, but fuck her if I’d give her the satisfaction of being right, which she always was. It burned my eyeballs like some sort of ingenious torture device.

I stomped down on the shovel and it pierced the dirt and hit something hard, like a rock. There are about a hundred thousand of those bastards planted in this weed-infested garden, so why not?

The shovel handle slipped through my moist and blistered hands, and speared me right in the adam’s apple. I rolled around among the prickly weeds and freshly turned stony soil, gagging. Just another day of recreation at Aunt Agnes’ Boarding House and Forced Labor Summer Camp.

I blamed it on my dick.

Ever since I grew hair down there, my brains puddled and flowed straight to my groin. Not that I was ever the smartest kid, but once puberty ambushed me, whatever intelligence I owned shifted from whatever useless class to finding opportunities to stroke my boner.

I’m embarrassed to write this down, but hell, every teenage boy beats his meat. I bet all the nonexistent wages I earned for my twelve hours of “ daily rehabilitation”every single guy does, gay, straight, black, Asian, Canadian. Even Carlos, claims he’s going to the seminary to be a priest, acts like he’s holier than Jesus. I just know he slaps the salami, probably while saying the rosary.

I stomped down on the shovel, and it sliced through the weed roots, until it collided with a rock. No surprise there, I’d personally encountered about a hundred thousand of those bastards in the two weeks I’d been digging up Aunt Agnes’ defunct garden.

No, the big surprise was the shovel handle sliding through my gloved hands and punching me in the throat, shoving my adam’s apple just about out the back of my neck..

I dropped like a fifty pound bag of cow manure, grunting like a rutting moose, thrashing around in the prickly evil weeds and the dirt clods and the freaking rocks. I’d finally found a comfortable spot, fewer sharp edges and less throbbing on my bruised windpipe, when that rusty, creaky voice popped my eyes open.

“Is it nap time, boy?” Aunt Agnes said. As usual, she was silent as an Iroquois warrior. She was as proud of her Native American heritage as she was of being the daughter of a big city fire chief.

I struggled to stand, wiping a crust of mud from my cheek. “Gaa,” I said, my voice gravelly with the poke, “Rocks.”

“You can curse the rocks, Mitchell. Or you can build a house with them. Makes no never mind to the rocks,” Aunt Agnes said. “It’s all in your attitude.”

My attitude was crappy, no question. Mom had dropped me off in this urban jungle with this pseudo- “Aunt” who I’d never met. Hell, she wasn’t even a real relative.. She said this summer expedition was to teach this fifteen year old boy self-reliance and inflict me with fresh air and exercise, and keep me from whacking off to porn all the time.

But the real reason, the reason why Mom didn’t want me anywhere near our house, was because we didn’t have one anymore.

I stomped down on my ancient shovel, and it sliced through the weed’s robust roots. Until it clanged against a rock. No surprise there, I’d encountered a hundred thousand of those immovable bastards in the two weeks I’d been digging up Aunt Agnes’ decrepit garden.

The shovel handle slid through my gloved hands and punched me in the throat, shoving my adam’s apple just about out the back of my neck..

I dropped like a fifty-pound bag of cow manure.

Grunting like a rutting moose, I thrashed around in the prickly weeds and the dirt clods and the murderous rocks. I sank into the craggy rubble. My bruised windpipe throbbed.

“Is it nap time, boy?” Aunt Agnes said. That sharp jab of a voice popped my eyes open. She’d snuck up on me as silent as an Iroquois warrior. She was as proud of her Native American heritage as she was of being the daughter of a big-city fire chief. Never mind the city was Detroit, more famous for its Devil’s Night mass combustion than the dusty legend of her dad.

I struggled to stand and wiped a crust of mud from my cheek. “Gaa,” I said, my voice gravelly from the poke, “Rocks.”

“You can curse the rocks, Mitchell. Or you can build a house with them. Makes no never mind to the rocks,” Aunt Agnes said.

Aunt Agnes wasn’t wrong about much, damn her, but she didn’t understand the malevolence of each stone in the soil. In three weeks I’d unearthed a six foot pile of them, bigger around than my arms could reach. And they sat gloating, smug, as their brethren maneuvered under my shovel blade. Those rocks were actively evil.

It was all about me, but it wasn’t. Which made it so fascinating watching Mom and Aunt Agnes duke it out. Not that it mattered who won, because, fuck both of them, I wasn’t sticking around in this inner city haunted house. Not one day.

Our drive to this urban wilderness was its own kind of awkward sparring. I sulked and steamed and shrunk inside my shell, because that’s what you do when Life takes a big dump on you, your mom catches you red-handed, red-faced and stiff-dicked in the act of jerking off like any 15 year old boy, and sentences you to exile to an urban hell-hole with a relative of dubious relationship.

Mom fidgeted and fumed and twitched her way through unfamiliar streets, pretending to know the way when we both knew her ties with this “aunt” were just as fake as her reason for shipping me there.

Her real reason was because she was losing the house. Her not-quite full-time job not enough to feed us and pay the mortgage. Maybe she thought she could shuffle all the mail stamped in ALL CAPS to the bottom of the pile, and ignore the constant barrage of phone calls from creditors she let go to voice mail until we had no phone service at all, and I would be too stupid to notice.

But I got it, Mom. Even if I was bringing home shitty grades, I was smarter than that. And I knew when you hooked up with that greasy narcissist of a dickhead, that he’d make you choose between him and me.

Only I didn’t think you’d choose him. Not so quick. Not after what we’d been through together. Not when he was so obviously a walking, talking tube of semen wrapped up in a cheap suit with a bulging button, not enough cologne and mints in the world to cover up his inner decay. Over your own kid.

Aunt Agnes stood firm in front of the screen door, like the last stubborn guard holding off the barbarian hordes storming the nursery. Or the nunnery. Or the nunnery nursery. Who gives a shit? She wasn’t letting us in over her ancient but very much alive decrepit body.

“I don’t hear from you for decades,” said the crab-faced old woman. “And then you show up with this surprise gift?” She cut her eyes briefly to me. They screamed disapproval. I was getting used to it.

The old wood of the porch stared me down, worn but hardened by decades of weather into stone. Not unlike the face of this crypto-relative, this “Aunt Agnes” I had never met. This was a house, and a face, that I would gladly escape from.

Which made it so fascinating watching Mom and Aunt Agnes duke it out. Not that it mattered who won, because, fuck both of them, I wasn’t sticking around in this inner city haunted house. Not one day.

Our drive to this urban wilderness was its own kind of awkward sparring. I sulked and steamed and shrunk inside my shell, because that’s what you do when Life takes a big dump on you, your mom catches you red-handed, red-faced and stiff-dicked in the act of jerking off like any 15 year old boy, and sentences you to exile to an urban hell-hole with a relative of dubious relationship.

Mom fidgeted and fumed and twitched her way through unfamiliar streets, pretending to know the way, when we both knew her ties with this “aunt” were just as fake as her reason for shipping me there.

Her real reason was because she was losing the house. Her not-quite full-time job not enough to feed us and pay the mortgage. Maybe she thought she could shuffle all the mail stamped in ALL CAPS to the bottom of the pile, and ignore the constant barrage of phone calls from creditors she let go to voice mail until we had no phone service at all, and I would be too stupid to notice.

But I got it, Mom. Even if I was bringing home shitty grades, I was smarter than that. And I knew when you hooked up with that greasy narcissist of a dickhead, that he’d make you choose between him and me.

The car rocked to a stop, and I finally had my answer. Mom was taking me to a haunted house. I pushed my way out, and the neighborhood smelled old, like the first whiff of a thrift shop. Even if I didn’t believe in ghosts, the place looked like it had held its breath years ago and had forgotten to let go.

Three stories of dead gray which might have been green in a past life. A covered porch with a swing and a rocking chair that bobbed empty in the hot July breeze. The steps groaned when Mom used them, so I jumped to the deck from the cracked sidewalk, just because I could.

“Mitch,” my Mom growled. “Don’t be such a boy.” I ignored her, my go-to.

She tried the doorbell, which didn’t move under her thumb and didn’t make a sound. I wondered what the doorbell used to sound like when it had juice, maybe spooky organ music, or a death-rattle scream? I kept my grin inside my head though; no one was getting a smile from me.

So she pounded on the wooden screen door frame. It rattled. Mom’s shoulders bunched-up and her fist tightened. I pitied the door for sponging up her blows; she hated being thwarted. She pounded like a punch-drunk woodpecker, settling for length over loudness. Whack whack whack whack whack whack whack thunk whack whack whack. She could be as annoying as me. Genetics.

The main door was open, so no air conditioning. Above Mom’s raised arm, the dim outline of two spirits studied her, until I focused--just a shawl and a suit coat draped on a rickety coat rack.

Finally, a shadowy figure hobbled out of the depths. It was long and thin, bent over like it was counting steps, and it used a cane to keep time. It turned out to be an old guy, startled gray hair over a brown face. The pounding continued as he slowly pulled the jacket off the rack and shrugged into it.

He made for the door, stood behind the screen.“Hold up, young lady,” he said. Either he was blind, or trying to be kind. Mom wore her mid-30’s like a funeral shawl.

Through the rusty screen it was hard to make out his dark face, but a look of amusement danced across his eyes, like whatever this was would be the start of a grand adventure, at least for him.

He broke into a huge smile and creaked open the door. Then he wasn’t a ghost at all, but he was old enough to start rehearsing.

“You are such a selfish girl.”

And that was it, the straw that choked the last sea turtle. And broke my cool.

I swallowed the words that rose from inside, stood, turned from Mom and strode away like I had somewhere important to go. And I did. Away from her.

My book tumbled to the floor. It made my teeth ache to hear it plunk, but I kept walking. Not stomping or kicking the furniture or even rolling my eyes into the back of my head and sighing like a busted parade balloon, just one step and then another. But my insides sizzled.

If my Mom was saying something, and she was always saying something, I didn’t hear it. Inside my head the screaming was loud enough to unfurl my pony tail.

I’m so selfish? Me? The girl living in a rent-by-the-week hotel room, uprooted from friends and home, while Mom desperately chased a dream of writing that ONE book that’d buy her happiness again. Writing a book! Talk about the ultimate gamble.

Not that she was totally unqualified. She had written a couple YA romances of modest success, a trilogy that shrank to two, and finally a sad standalone that went out of print before the year was out. And that.was four years ago.

Since then nothing. Well, crying after dark and drinking wine after noon and enough manuscripts, partially completed and permanently filed that virtual forests would have been leveled had all those lost words met paper.

She blamed the drought on me turning a teenager, ignoring the affair and divorce, the increasingly shitty jobs and sketchy apartments and shady man-friends.

And I’d take some of the blame, sure. Me of the soul-wrenching sighs and the eye-rolls so athletic I could scan my brain on the way around. I didn’t particularly like school, my real friends gone two years and three schools ago. I didn’t like life.

I was big-boned like my Dad, and like my Dad I was disappointed with the rest of my family. Unlike my Dad, I couldn’t run away. Yet.

But I wasn’t the one who used up the last of our wheezing bank account to go to this writer’s retreat, out in the middle of Creepyville, USA. I didn’t choose this old, worn-out twisty-turny maze of a hotel, likely the last bed I’d get to sleep in before the back seat of our car was my home. I was definitely not the one ordering a daughter to ‘Just be patient’ as what was left of her world swirled down the toilet bowl.

But I’m the selfish one?

My mad had drained out, and I realized, not for the first time today, that I didn’t know where I was. In this hotel that specialized in long, dark corridors that led to darker, dingier hallways.

If I was deliberately trying to wander as far away from my annoying mother as I could in ten minutes, I’d done an excellent job of it. If I was hoping to find our room, or even a recognizable part of this hotel, I’d failed. Again.

There were doors lining the hallway, but the numbers meant nothing to me, and I realized with a lurch in my stomach that I had left my room key inside my book to mark my place.

My place being, apparently, not of this world.

The overhead fluorescents flickered, dark rings at the tube ends marking inevitable decay and coming darkness.

Extend your weekend of enrichment with a Monday morning keynote and breakout session with author and educator Jennifer Seravallo. She opens the final day of the Michigan Reading Association’s 2020 annual conference, Monday March 16, with a general session from 8:30-10:00 am.

Jen began her career in education as a NYC public school teacher and later joined the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project at Columbia University. Through TCRWP, and now as an independent consultant, she has spent over a decade helping teachers across the country to create literacy classrooms where students are joyfully engaged and the instruction is meaningfully individualized to students’ goals.

Jennifer Serravallo is the author of New York Times’ bestseller The Reading Strategies Book as well as other popular Heinemann professional books, The Writing Strategies Book; Teaching Reading in Small Groups; and The Literacy Teacher’s Playbook, Grades K–2 and Grades 3–6. Her newest books are Understanding Texts & Readers, and A Teacher’s Guide to Reading Conferences.

In Spring 2019, Jen’s new Complete Comprehension: Fiction and Complete Comprehension: Nonfiction was released. This assessment and teaching resource expands upon the comprehension skill progressions from Understanding Texts & Readers and offers hundreds more strategies like those in The Reading Strategies Book.

Additionally, Jen is the author of the On-Demand Courses Strategies in Action: Reading and Writing Methods and Content and Teaching Reading in Small Groups: Matching Methods to Purposes, where you can watch dozens of videos of Jen teaching in real classrooms and engage with other educators in a self-guided course.

Jen holds a BA from Vassar College and an MA from Teachers College, where she has also taught graduate and undergraduate classes.

Below, MRA Conference Chair Colby Sharp review’s Jen’s book, Reading Conferences.

Register now (through Eventbrite) to experience General Session Speakers including Ernest Morrell, Sara K. Ahmed, Cornelius Minor and Jennifer Serravallo. Also, choose to attend sessions with Featured Speakers such as Chad Everrett, “Gholdy” Muhammad and John Schu, or Featured Authors including Donalyn Miller, Tara Michener and Carrie Pearson.

For more on the conference, visit our 2020 Annual Conference page.

Posted in: 2020 Conference, Conference News

Cornelius Minor closes the first day of the Michigan Reading Association’s 2020 annual conference in Detroit with a general session from 4-5:30 pm on Saturday, March 14.

He is a Brooklyn-based educator. He works with teachers, school leaders, and leaders of community-based organizations to support equitable literacy reform in cities (and sometimes villages) across the globe. This blog post from ILA highlights 5 reasons why educators love Cornelius Minor. His latest book, We Got This, explores how the work of creating more equitable school spaces is embedded in our everyday choices—specifically in the choice to really listen to kids.

He has been featured in Education Week, Brooklyn Magazine, and Teaching Tolerance Magazine. He has partnered with The Teachers College Reading and Writing Project, The New York City Department of Education, The International Literacy Association, and Lesley University’s Center for Reading Recovery and Literacy Collaborative. Out of Print, a documentary featuring Cornelius made its way around the film festival circuit, and he has been a featured speaker at conferences all over the world.

Most recently, along with his partner and wife, Kass Minor, he has established The Minor Collective, a community-based movement designed to foster sustainable change in schools.

Follow him on Twitter @MisterMinor

Register now (through Eventbrite) to experience General Session Speakers including Ernest Morrell, Sara K. Ahmed, Cornelius Minor and Jennifer Serravallo. Also, choose to attend sessions with Featured Speakers such as Chad Everrett, “Gholdy” Muhammad and John Schu, or Featured Authors including Donalyn Miller, Tara Michener and Carrie Pearson.

For more on the conference, visit our 2020 Annual Conference page.

Posted in: 2020 Conference, Conference News

Sara K. Ahmed opens the 2020 Michigan Reading Association annual conference in Detroit, speaking Saturday, March 14, from 8:30-10:00.

She is the author of Being the Change: Lessons and Strategies to Teach Social Comprehension. In her book, she identifies and unpacks the skills of social comprehension. She also co-authored Upstanders: How to Engage Middle School Hearts and Minds with Inquiry. You can hear more of her recent thinking in this Heinemann blog post/podcast.

I am convinced that every class of kids I work with is filled with change agents who will make this world the one we teach toward. I believe that my students will carry the work of doing right by this world into their own lives.

I’ll bet you believe this about your kids, too.

—Sara K. Ahmed

Sara is a literacy coach at NIST International School in Bangkok, Thailand. She has taught in urban, suburban, public, independent, and international schools, where her classrooms were designed to help students consider their own identities and see the humanity in others. In the interview below, MRA conference coordinator Colby Sharp reviews Ahmed’s book, Be the Change.

You can follow her on Twitter at @SaraKAhmed.

Register now (through Eventbrite) to experience General Session Speakers including Ernest Morrell, Sara K. Ahmed, Cornelius Minor and Jennifer Serravallo. Also, choose to attend sessions with Featured Speakers such as Chad Everrett, “Gholdy” Muhammad and John Schu, or Featured Authors including Donalyn Miller, Tara Michener and Carrie Pearson.

For more on the conference, visit our 2020 Annual Conference page.

Posted in: 2020 Conference, Conference News

Dr. Ernest Morrell opens the Sunday morning general session of the Michigan Reading Association’s annual conference on March 15, 2020.

Currently the Director of the Center for Literacy Education at the University of Notre Dame, Dr. Morrell has written more than 80 articles and has authored eight books. Among those titles, Critical Literacy and Urban Youth, Becoming Critical Researchers, and Linking Literacy and Popular Culture are among his most popular books.

Dr. Morrell is chair of the Planning and Advisory Committee for the African Diaspora Consortium and sits on the Executive Boards of LitWorld and the Education Democracy Institute. He has won numerous awards and held many prestigious educational positions, including service as a past-president of NCTE.

Register now (through Eventbrite) to experience General Session Speakers including Ernest Morrell, Sara K. Ahmed, Cornelius Minor and Jennifer Serravallo. Also, choose to attend sessions with Featured Speakers such as Chad Everrett, “Gholdy” Muhammad and John Schu, or Featured Authors including Donalyn Miller, Tara Michener and Carrie Pearson.

For more on the conference, visit our 2020 Annual Conference page.

Posted in: 2020 Conference, Conference News

SCHOOL VISIT SESSION MARCH 2020

How to conduct a school visit

How WE do ours

How to give your students the most benefit

Before

During

After

MONEY

Unfortunately for most kid’s book creators, school visits help to pay the mortgage.

Some authors may not charge, but instead require a certain number of books sold.

Some beginning authors may use your classroom or school to work out their presentation.

Some publishers may schedule school visits on book tours. The visits may be free for the schools. But publishers have cut waaay back on those kinds of expensive promotions.

Proven that there is less appreciation on both sides of the presentation if the event is free.

PTOs

Good parent-teacher organizations can bankroll school visits.Some fortunate schools with robust PTOs can schedule more than one visit per year, or bring in separate presenters for different grade levels.

GRANTS

A grant writer is worth more to your school than quality coffee in the break room. You can learn to write grants yourself, or find an eager young staff member who

.jpg/:/cr=t:2.83%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:94.34%25/rs=w:388,h:194,cg:true)

SOME WAYS TO MESS WITH A PERFECTLY GOOD FAIRY TALE

Change the Time Period

l Present day

l Distant future

l Dinosaur-time

l Middle ages

l Back when there was magic

l Horses and buggies

l When animals could talk

Change the Setting

l Haunted house or graveyard

l Jungle

l Outer space

l Under the sea

l North or South Pole

l Uninhabited island

l Your school or backyard

Add Props

l Magic wand

l Picnic basket

l Flying carpet

l Fairy wand

l Winged shoes

l Talking cat

l Peanut butter sandwich

Use a New Point of View (POV)

l Exchange the hero and villain

l From a secondary character

l From a bemused narrator

l From an insect, bird or animal

l From a tourist or visitor

l From a judge or police officer

l From someone who has to clean up, repair or undo the mess

l From a visitor from another galaxy

Superpowers

l Flying

l Shooting bolts of lightning from eyes

l Invisible

l Super fast

l Reads minds

l Shape-shifter

l Extra smart or strong

Limits to those Superpowers

l Water

l Smelly feet

.jpg/:/rs=w:370,cg:true,m)

.jpg/:/rs=w:370,cg:true,m)

.jpg/:/cr=t:9.68%25,l:9.68%25,w:80.65%25,h:80.65%25/rs=w:370,cg:true,m)

Eric has published two memoirs to great acclaim

Tiffany has grown her crochet into a massive empire. Plus, she writes.

1972

Brothers we, oh South Lake High

Until the end doth come.

Like wind and air together fly

Like fingers to a thumb.

So now I'll tell you true, my friend

How much I do adore you.

If noses were used to defend

Then I would blow mine for you.

SEVEN OLD GEEZERS

SUNG TO THE TUNE OF

SEVEN OLD LADIES

>

> And it's oh dear, what can that odor be?

> Seven old geezers are drunk and disorderly.

> They were rejects from Gentleman's Quarterly.

> Somebody call the police.

> {puh-leeze!} (optional).

>

> The first old geezer was old Mr. Hadder,

> He was plagued with an impatient bladder.

> When his zipper got stuck, well, it didn't matter.

> So somebody call the police.

>

> Refrain.

>

> The second old geezer was mountaineer Mungee.

> He scaled the tank, reached the top, took the plung-ee.

> Next time, sir, use a much shorter bungee.

> Will somebody call the police?

>

> Refrain.

>

> The third old geezer was old Mr. Fleemer.

> Driven to drink, he was quite the day-dreamer.

> Asleep at the wheel of his porcelain Beemer

> Can somebody call the police?

>

> Refrain.

>

> The fourth old geezer was old Mr. Wrangle.

> When he took a leak he would just let it dangle.

> No problem with distance but always with angle.

> And somebody call the police.

>

> Refrain.

>

> The fifth old geezer was a visiting Haitian.

> He lifted the lid 'cause it weren't defecation.

> It fell with a thud and they called it castration.

> Somebody call 9-1-1.

>

> Refrain.

>

> The sixth old geezer was old Mr. Wurinell.

> He wrote obits for the Lansing State Journal.

> 'Til he fell asleep with his head in the urinal.

> Be kind when you write him up, please,

>

> Refrain.

>

> The seventh old geezer was old Mr. Spinner.

> He made a bet with a Mexican dinner.

> Montezuma's Revenge was the eventual winner.

> Did anyone call the police?

>

> Rousing Last Refrain.

Here I am, I'm in the street,

Cars are honking at my feet.

I could crush them with my toe,

But I'll be good and let them blow.

The buildings are so tall and spare,

I clamber to a point up there.

Airplanes buzz my ears like flies.

But I won't swat those strafing guys.

I leap and bound from peak to spire.

I reach the top and then soar higher.

The moon could be my basketball.

I'll leave it there, it's kinda small.

The fiercest beasts turn tail and flee

If they should sniff a whiff of me.

It's then the mythic monsters cry,

The T-Rex begs, the dragons fly.

The ocean is my swimming pool,

But I don't dive in as a rule.

I toy with boats on choppy seas.

Oh, I could sink them if I please.

I'd pull the plug, it's in my reach,

And make the waters one big beach.

I frolic in the dunes instead,

And make a sculpture of my head.

The weather is afraid of me.

I part the clouds so I can see.

I push the wind back with a fart.

The sun asks me if day can start.

I am a big and brawny brute:

Terror in a monkey suit.

My quickness is too fast to see,

I'm back before you're missing me.

I gulp with gusto, slake my thirst,

My etiquette might be the worst.

I could offend society.

I could, but that's not really me.

I can't sit still, I'm made to move.

Got lots to do, but not to prove.

I'm wild and strong and brave and free.

I don't believe in gravity.

I grapple mountains into dust.

I crumble bridges into rust.

I am a huge vindictive force,

Or could be, if I chose, of course.

No prison walls can capture me,

If that's not where I want to be.

No laws of science, God or man,

Apply unless I say they can.

There's just one thing keeps me in check,

To say my prayers and wash my neck.

I'd be destructive as a bomb,

Except I love, and fear, my Mom.

Charlie Barshaw

For Ruth, Cayden and Lisa, his mom.

Posted by charlie b. at 8:15 AM

Off-color version of an epic quest to drink more beer.